News & Media

From 2012 to 2020, Fr. Paul Mankowski, SJ delivered hundreds of lectures and master classes at the Lumen Christi Institute. Seeking to share the depth of his scholarship, this podcast offers many of his lectures (edited for coherence and quality) to the public in digital format for the first time. The first season will feature a course that Fr. Mankowski gave on Joseph Ratzinger’s Jesus of Nazareth and dozens of lectures centered around the books of the Bible (including Genesis, many of the prophets, the Gospel of Matthew, and St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans). Episodes will be released on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays from September through December. To conclude the season, we’ll offer one or two interviews with people who knew Fr. Mankowski well and can offer an entry point to his person and scholarship.

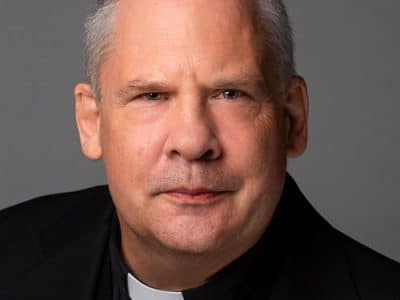

Fr. Paul Mankowski (1953 – 2020) was a brilliant essayist, a singular wit, and a devoted son of the Church. Born in South Bend, Indiana, he put himself through the University of Chicago while working summers in a steel mill.

Free and open to the public. Registration is required. Contact us with any questions. Note the time for this event has been changed from 4:30 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. In discussions of the history of the philosophy of human rights,

In partnership with CREDO, the Lumen Christi Institute is cosponsoring a monthly invite-only CREDO Econ and CST Virtual Workshop. This interdisciplinary workshop will take place online the first Friday of each month and feature papers addressing the intersecting domains of

The following memorial tribute for Thomas Levergood was submitted by Professor Jennifer Frey, delivered at the wake held for Thomas at Gavin House, August 13th, 2021. — I met Thomas Levergood in 2010 here in Hyde Park. Gavin House didn’t